A little background…

Over the past two decades, pressures on colleges and universities to demonstrate value have intensified. A number of stakeholder groups, including, but not limited to, accreditors, policy makers, employers, and students and their families, want to know that they will receive a “good return on their own and society’s educational investment.”1 For higher education institutions, the calls for evidence sometimes translate into a need to demonstrate the high-quality of existing degree programs, as well as to more clearly communicate efforts to maintain and continuously improve programs in ways that resonate with stakeholders.

But, what does a “high-quality degree program” look like? How is “quality” defined and measured? What evidence should be presented to demonstrate quality? And, how can that evidence be adequately collected and effectively communicated?

Turning to the literature on college quality and program quality, what we find is, essentially, a lack of agreement. There are many definitions of quality, and approaches to measuring quality are quite varied in terms of indicators and instruments employed. As may be expected, quality indicators are often prioritized based on the values and interests of the stakeholder group conducting the inquiry.2

With so much variation, where should college administrators and faculty start addressing program quality? How might they think about degree program quality in a tangible and useful way?

The data…

OCCRL’s Applied Baccalaureate research team has taken its exploration of program quality into the field over the past 16 months, where we visited over 20 higher education institutions and organizations that are a part of six applied baccalaureate (AB) degree pathways. We interviewed a variety of stakeholders (e.g., degree program administrators and faculty, current students, graduates, advisory board members, local employers) to understand how AB pathways are designed, organized, implemented, experienced, and evaluated. Gaining a deep understanding of issues surrounding program quality is critical to our National Science Foundation, Advanced Technological Education (NSF-ATE) project. Guiding questions included:

- How do stakeholder groups perceive program quality?

- What steps should program administrators and faculty take to establish, demonstrate, improve, and communicate degree program quality?

The emerging ideas…

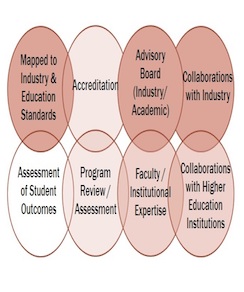

We listened closely to the narratives of the diverse stakeholders interviewed during our site visits, and reflected on their stories in light of the literature on college program quality. What emerged for us was a picture of program quality as a multi-dimensional construct.

There are a variety of lenses through which the quality of a particular degree program can be considered, such as:

- Mapping courses to industry or educational standards

- Engaging in accreditation (regional, departmental, or program)

- Consulting an advisory board (with industry and/or academic members)

- Building collaborations with industry

- Building collaborations with other higher education institutions

- Relying on the expertise of faculty and administrators

- Engaging in program review or assessment processes

- Assessing student outcomes

These are just a handful of examples. Many more can be found in our presentation materials from our recent presentation at the 2013 HI-TEC Conference (PDF of PowerPoint Slides | Handout).

We would argue that a single program is not likely to address to all program quality dimensions at any one moment in time. Further, some program quality dimensions may not ever be addressed (e.g., some fields of study do not have established educational standards). There are too many options; addressing to all program quality dimensions could drain resources and make it difficult to keep up with other aspects of program operation.

We also argue that, despite their variability, each program quality dimension has value. One dimension is not necessarily “better” or “more important” than another; rather, each speaks in a different manner to different stakeholder groups. Each dimension holds meaning within some fields of study or professional areas more than it does in others. In short, context matters.

We also certainly welcome your thoughts and feedback.

References

1 Guskin, A. E. (1994). Reducing student costs and enhancing student learning. Change, 26(4), 22-30.

2 Stephan, J., Hoogstra, L., Davis, E., Garcia, A., & Miller, S. (in press). An Inventory of Definitions and Measures of College Quality: A Summary Report for Members of the College and Career Success Research Alliance. Naperville, IL: REL Midwest.

Sullivan, T. A., Mackie, C. Massy, W. F., & Sinha, E. (2012). Improving measurement of productivity in higher education. Washington, DC: National Academies Press